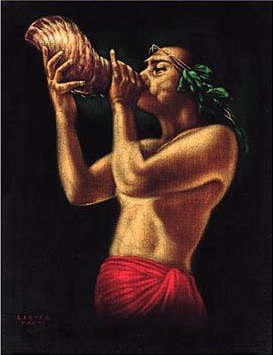

Velvet paintings have a bad name, and most of them deserve it. Crude, mass-produced pictures of Elvis, JFK, and dogs playing pool are the norm. But velvet is a difficult medium to work with, and Edgar William Leeteg had a facility with it that approached genius. Inexpertly applied, paint will cake and clog the velvet nap. The black velvet dye can bleed even the brightest colors to muddy browns and dull, dirty grays. Leeteg knew black velvet like an astronomer knows the night sky. With an artist’s instinct, he painted each individual strand, adding thin layers of color one at a time. He used a limited palette—only seven colors and white—but created results so rich that one observer said that he “painted with light.”

Known to many as the American Gauguin, Leeteg (1904-1953) led a Jack Kerouac life, ghost-written by William Burroughs. An adventurer by nature, he fled civilization to lead a wild life in Tahiti. Even in a culture not known for its puritanism, he stood out, drinking, fighting, and wenching more than any six men. He once described himself as a “fornicating, gin-soaked dopehead.”

But his carousing was a calculated pose to promote his art, and the staggering quantity of paintings he left behind (an average of three a month for 20 years) suggests that he was as much a workaholic as an alcoholic. A butcher’s boy and the grandson of a graveyard sculptor in East Saint Louis, Leeteg picked cotton, herded cattle, and did factory work until he landed a job at 22 as a sign painter in Sacramento. When the Depression hit and the work ran out, Leeteg took a small inheritance and set sail for Tahiti with brushes stolen from the sign company and six mayonnaise jars full of paint. His first commissions—posters and lobby ads for theaters—barely put food on the table. He lived hand to mouth, restlessly experimenting with different painting surfaces, including wood and cloth. Finally, he hit on velvet—and struck gold. Leeteg circulated the story that his first velvet “canvas” came from a mortuary, suggesting a discovery born from desperation. But he knew velvet’s potential; in museum visits, he had seen Renaissance and Victorian velvet paintings. Velvet became the perfect medium through which to express Leeteg’s love of Tahiti’s sensual beauties—the natural light, the landscape, and especially the native women.

Paradise painted (Seattle Weekly)